One of the great thrills of my life was being hosted by Antoinette Beiser at Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, while I was researching Percival’s Planet — and being led into the dusty basement archives of the observatory. I wrote the following scene — which didn’t make it into the book ultimately — after having experienced something like it in person.

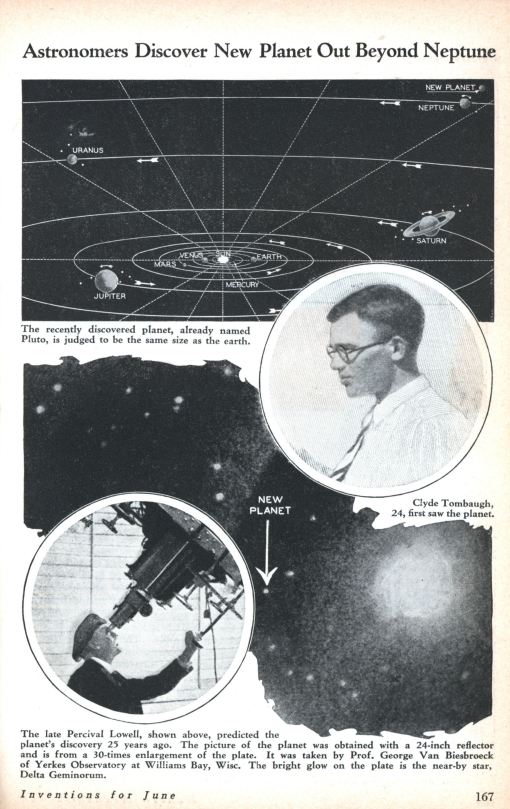

Here, the young Harvard mathematician Alan Barber is being taken into the observatory vaults by the Director, Vesto Slipher — and being given access to Percival Lowell’s raw calculations — the work that convinced Lowell that a 9th planet was out there, somewhere, and that led to his publication of Memoir of a Trans-Neptunian Planet…

None of this made it into the novel, but the book does contain a scene — the grandchild of this scene — in which Slipher hands Pericval Lowell’s notebooks over to Alan Barber.

The papers are as I describe them here, and the boxes — and the dust.

* * *

Vesto Slipher switches on the basement light and twirls the key on its length of twisted wire. “This way,” he nods.

The basement smells of coal dust, firewood, and developing fluid. They walk the length of the hall to a steel door. Alan has never seen it opened. He has assumed it housed some of the building’s works. Slipher works the key into the lock. “Percy would send us these every few months, you know,” Slipher tugs the door open onto a damp, sweet-smelling darkness. “So we ended up with quite a collection.”

He flicks on a light. Inside is a long, low basement vault with a cement ceiling. Junk everywhere: discarded equipment with snipped wires, motors and housings, ladders with splintered rungs, a Victorian dollhouse split open along the green-papered parlor, dead fans. On a shelf stands a long row of slumping notebooks, crimson and emerald green. Slipher tugs the first one from the row, careful not to send them all to the floor.

“Percy’s notebooks,” he says.

“From the Memoir.”

“That’s right. All the figures the computers gave him went into these. He’d finish with one and put it in an envelope and send it out. He always thought he’d look at them when he came out, but – ” The director places his hands in his pockets, tips back on his heels. “You know, he’d have changed his mind again by the time he got out here. He was very good, you know. Just as good as anyone you’ve got there now. But he was sort of – you know, enthusiastic.”

Alan finds it hard to speak: it is the Aladdin’s cave of Lowell Observatory. “Some trouble,” he manages.

“Some trouble,” Slipher agrees, mildly. He hands Alan the key. “It’s in order. Starting back there. All his calculations going back thirty years almost. Off and on. What we have, anyway. They’re yours, if you want them. For whatever the hell they’re worth.”

He finds his breath. “Thank you.”

“That’s what you think,” Slipher answers.

In another minute he is alone, in the middle of the night, still blurry with liquor. His mouth tastes sweetly of raw spirits. A single bulb burns in a wire cage. At the musty back of the vault he slides down the box marked Mar 17 – 88, taking its weight into his arms. The box is covered with dust. He sets it on the library table, blows off the dust, tips back the cardboard lid.

Inside sits a gray paper folder, the first of a stack. He teases his handkerchief out of his back pocket and wipes his hands on it to remove the dust, then lifts the folder out. He sets the folder on the table. He opens it.

Someone’s purposeful black pen, guided by a ruler, has drawn a straight line across the top of the page. Above this line, in a curling hand, is written Jupiter – July 1793 – Maddox Obsv. Then comes a long fall of trigonometry that represents the attempt of someone in 1888 to determine whether Jupiter was where it was supposed to be, when observed doing what it was doing in 1793.

He follows the calculation with his forefinger.

Turns the page.

He follows.

He sinks into the chair, turns another page.

Another.

In an hour he has gone halfway through the folder. At some point as though he is sitting an exam he unclasps his Santos from his wrist and sets it before him. He has a pencil in his hand now and is making notes on the inside cover of the gray folder. The computer, whoever she was, has not made any errors, not that Alan can find, anyway. He admires the fine, womanly hand that falls with a sort of chiming inerrancy down the page, page after page, as she turns one, then another observation this way and that through the method of least squares, and he can’t help it, he thinks of Florence, thinks of this sort of exact feminine facility, a sort of equivalent to stitching, in that it is invisible, but an error anywhere is enough to ruin the entire effort.

All these boxes and boxes.

He looks out the door of the vault, down the empty basement corridor. If Dick were to discover him here he would give him the business for sure. Alan has a vision of him loping into view, trailing his fingers on the vaulted cement ceiling.

But Dick is gone.

A queer feeling comes over him that the ninth planet is truly out there somewhere. Something in the cavey, monasterial feel of this basement tells him this. It is a sort of sum of these variant parts: the madman who ordered all these numbers to be set down, the years of painstaking feminine labor in the walnut-paneled computer room on Halward Street in Cambridge, all the girls with their inkwells and linen blotters, plus this desert air, this piney hilltop, the crazy Injuns in their reeking blankets, their blackfly horsewagons, and the airstrip at the edge of town, the train dragging its lighted cars away.

All of it adds up somehow to a sweet little mysterious certainty.